“Watashi kirei?”

You blink. What did she just say? You ask her to repeat herself.

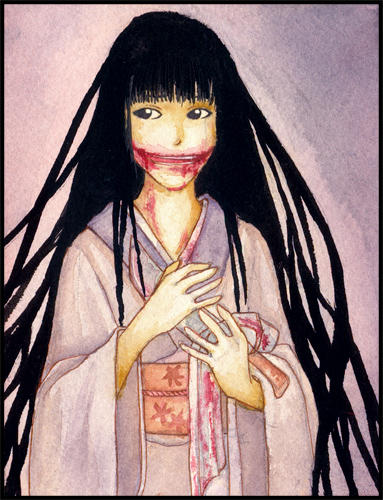

“Am I beautiful?” She asks. How abrupt, how...odd. Suddenly on edge, you swallow heavily and say you can’t tell, due to the face mask, but she seems pretty, what with her long black hair and wide eyes.

She reaches up and pulls down her face mask. What greets you is a wicked smile, full of pointed teeth. Her cheek is split open in the most hideous of Glasgow smiles, blood dripping down her chin. You freeze. She opens her arms, revealing a sharp knife.

“What about now?” She asks. And then she lunges at you, slashing wildly with the knife.

You run, a blitz of speed and fear, wanting nothing more than to get away from this horrible lady. Wishing you had never taken this path home. And praying she doesn’t catch you.

You have just met a Kuchisake-onna, one of the most well known, and feared, monsters in Japan. And no, telling her she’s pretty will not stop her bloodlust.

The tale of the Kuchisake-onna might be one of the most prevalent in all modern Japan. A recent survey showed that upwards of 75% of schoolchildren know of her, and have been warned to avoid lone women wearing face masks, especially after nightfall. Now while the odds of that might seem low, it must also be taken into account that the practice of wearing face masks in Japan is actually quite common, a method employed by many to ward off illness. Now imagine being a child, and meeting someone like this. Imagine being the woman in the mask.

The Kuchisake-onna is hardly a recent addition to the yokai pantheon, but she has experienced a resurgence in the last 30+ years. Originally a Heian period tale of infidelity and revenge, it has morphed and twisted itself into a modern-day warning about some of the lengths people go in pursuit of beauty, no matter what the cost. There have been anime and movies made about her. There have even been recorded “warnings” from the yokai herself. And, like many yokai, she is a cautionary tale, rooted in human behavior, that scares and informs at the same time.

The origins of the tale first appeared during the heyday of Japanese upheaval. The Heian period, which gave birth to a good deal of yokai still found in Japan, was a time of war, revolution and drastic social changes. Samurai loyal to feudal lords clashed over land, the first shogun enthroned himself as the military leader of the nation, and the ideas of honor and loyalty began to appear in Japanese texts. Into this world came the tale of a beautiful woman married to a powerful samurai. He was devoted to his wife (or possibly concubine, the story is a bit murky on those details), and she to him, at least outwardly. In secret, she had taken a lover, and was performing acts unfit her station as the wife of a loyal, just man. Upon discovering this, the samurai took his sword and slit her mouth open, decrying “Who will find you beautiful now,” and casting her out. Unable to find a lover or a new husband to care for her unfaithful nature, she died and her spirit returned as a monster that stalked the land, exacting violence to sate its wayward nature.

The old tale of the Kuchisake onna fits perfectly in line with the social climate of Japan at the time. Loyalty and fidelity have always been important to the Japanese, but samurai were seen as the pinnacle of this concept of duty, faithfulness and honor. While what the samurai did to her would be considered appalling by our modern standards, in that time period, it would have been acknowledged, or even encouraged, as a just act. Likewise, her selfish nature, itself evidence of her sinful soul, would have reappeared on Earth to wander, as many such souls did at the time (a very famous one being the Wanyudo, but that’s another story...)

This story would likely have been very popular at the time, and possibly straight through into the Bakufu era, when such notions were codified and encouraged, but it faded away. Perhaps it was too regional. Perhaps it had served its purpose. The tale still slid into obscurity until the 1970s, when it re-emerged with a new spin, and new warning to tell.

Fast forward to the 1970s. A child, on his way home from school, is approached by a woman in a face mask. She asks him if he thinks she is pretty. Being a child, he shrugs. The woman pulls her mask down, revealing the hideous smile, and asks him again. The story ends there, but it’s more than likely the child survived, seeing as how the story spread through the schoolyard culture like wildfire. Childish imagination? Possibly. Or maybe the Kuchisake-onna was back.

The modern day tale has as many variations as one could expect from something undergoing a resurgence in relevance. Stories of a woman killed by gang members to a botched surgical procedure abound in different areas of Japan, speaking to a good many cautionary tales to be learned from this old yokai.

One such story, popular in Tokyo, speaks of a girl, alone at night, who runs afoul of a biker gang. They chase her on their motorcycles, ambush her in a side alley and proceed to rape her. After the deed is done, one story claims one of the bikers cuts her face to nobody else will find her beautiful. Another claims her mind was broken by the torturous ordeal and she does it to herself to prevent another such assault. Yet another claims the stink of the pomade worn by the gang members drove her to madness and she stalks out people who wear the stuff to exact revenge. But the idea behind this tale is the same: young women should avoid going out at night alone, especially if they are pretty. The loose morals of the biker gang coupled with the apparent innocence of the victim play out like the slasher films of the late 70s and 80s: the world is dangerous, full of disreputable types, who will not hesitate to cause harm, because they have no morals. Not exactly the same as, say, a Freddy Kreuger or Jason Vorhees, but still a warning on traveling alone and the importance of modesty. This also could lead to the face mask idea: wear a mask so they cannot see your face, and you are less likely to be a victim. This is only speculation, but based on the horrific nature of this story, it seems to fit.

|

| Why so serious? |

It is easier to see the inspiration behind this tale of the slit-mouth woman: be satisfied with your own looks, and don’t cut up your face in the name of beauty. Indeed, beauty does play a large role in Japanese art and folklore, as well as in fashion trends. And, like many other cultures, beauty is to be celebrated. Beauty has also had its fair share of negative connotations over the years. But this tale of the Kuchisake-onna is a warning to the extremes some people go in the name of “perfection.” It’s one thing to use conventional means to make ones self look more presentable, but where does that line end? How much is too much? Surgery, itself a dangerous act, is where the line should be drawn, at least according to this tale. Let your body remain natural, leave it alone, and be content with who you are. Because toying with nature might leave undesired effects. Or possibly a yokai.

So the next time you are walking down the street and you see a woman in a face mask...don’t run away. It’s terribly rude, and you don’t want to offend her.

I don't remember the last time I was so engrossed in a blog post. Thanks for writing and sharing this, Charles!

ReplyDeleteThe story is very interesting. This is my first time to hear about Kuchisake-onna. So what happens if your date looks like Kuchisake-onna? I will definitely run too.

ReplyDeletealt com